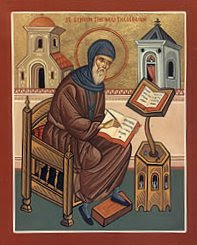

St. Symeon the New Theologian

There is a particular spiritual

sublimity that seems to glow from the pages of early Christian theology and

mysticism in their linkage of the Trinity and contemplation. One gets a sense of mystery and profundity

that is rarely found today. In fact I

think linking the Trinity to spirituality in most literature usually ends up as

little more than the affirmation of the platitude that God is community. But even with that necessary affirmation of

our communal God, I think the difference between say, St. Symeon, and many recent

invocations of Trinitarian spirituality and theology is the difference, crudely

put, between first and third person perspectives.

Often

God-as-community is spoken about in the third person, so to speak, as an

“object,” or reified set of criteria, which can then be utilized as a sort of

paradigm for community. The church then,

in a sense, becomes a sort of “deictic,” sign of this Trinitarian

community—which in and of itself is unobjectionable. But mere deictic “correspondence,” with its

Trinitarian “referent” always contains a dangerous irony in that while it is an

attempt to re-incorporate Trinitarian thought into theology, it nonetheless

keeps the Trinity at bay as a sort of quasi-exterior exemplar or

archetype. It “abstracts,” the trinity

from the actual economy of salvation to create an “ideal type” of communal

structure immanent to the Godhead itself which then serves paradigmatically as

a precedent for certain sorts of ecclesial structure.

Symeon does not

speak in this manner however. Whatever

he might think of the Trinity as a social criterion (and I think at many levels

he would find much to both like and dislike), the fact is that it appears for

Symeon the very recognition of the

mystery of the Trinity itself, is already

to be caught up into its operation and economy. He does not—and indeed cannot—stand at a

distance, as it were, from the Trinity to view it as a “criterion,” at all. It is telling that he uses the term “outer

wisdom” to speak specifically of illegitimate natural-philosophical approaches

to God. These literally have an

“objectifying” tendency where they cause God to stand “outside,” us as an

object of the intellectual gaze. Its

counterpoint for Symeon is the “interior” wisdom given by the Spirit (which

appears to be none-other than the Spirit itself). The Trinitarian relations cannot be modeled

point for point (or however analogously) in an ecclesial

“correspondence,”; the church is

Trinitarian not in this sort of abstract equivalence, but is caught up into the

life of the Trinity itself. “These are mysteries,” he writes, “which are

unveiled through an intelligible contemplation enacted by the operation of the Holy Spirit in those to whom it has

been given—and is ever given—to know them by virtue of the grace from on high.”

(114) and “For if no one knows the Son except the Father, neither does anyone

know the Father except the Son and whomever the Son may wish to reveal the Father’s

depths and mysteries to. In effect, He says ‘My mystery is for Me and

My own.’” (Ibid.)

As Moderns I do

not think we have yet escaped our tendency, however good our intentions, to

view the Trinity (and all doctrine) as “data” to assent to. Thus when a modern says “we accept the

Trinity by faith alone,” and when Symeon says the same thing (113) two very

different things are meant. The modern

means by it “I (subject) believe (in order to be orthodox) in the Trinity

(object).” Or “I (subject) will act in

community (in order to be orthoprax) analogous to the Trinity (object).” What Symeon seems to mean by “one instead

accepts [the Trinity] by faith alone” is “God has incorporated me into Christ

by the Spirit before the Father.” One

cannot “know” God by our own power, or even (Evangelical sensibilities be

damned!) “from just reading scriptures (!).” (113) Rather this knowledge is an indication that

Christians are “these…the ones who, moved by the divine Spirit, know the

equality of honor and union of the Son with the Father.” (115) The logic being

only God can reveal Himself, thus if a human comes to know God, this is God

acting through the human, God is “knowing himself,” as it were, through man. God is in a sense both subject and object in

the circle of knowing. We are bound to

the Trinity only in a recognition of the prior gift and presence of God working

already in us.

In fact one can

say that the Trinity, far from being a model of action per se, is invisible to

those who act in evil. “God has blinded their [the evildoers] intellect and

hardened their heart, so that seeing they see not, and hearing they do not

understand.” (116) The Trinity is not a

model for proper being in the sense that we understand “model,” either in a

physical or a metaphorical sense as an “exemplar” to be followed (a blueprint,

a criteria, etc…). Rather the Trinity

is, to use contemporary idiom, the “grammar” of proper Christian action already

underway through the initiation of the Spirit.

Thus the catenae of Symeon’s questions:

Have you, O’brother, renounced the

world and what is in the world? Have you

become one who possesses nothing, and submissive, and a stranger to your own

will? Have you acquired meekness and

become humble? Have you fasted to the

supreme degree, and prayed, and kept vigil?

Have you acquired perfect love for God, and have you regarded your

neighbor as yourself? Do you intercede

with tears for those who hate and wrong you, and are hostile to you, and do you

pray that they may be forgiven… (117)

While

these exhortations in no “specific” sense sound Trinitarian (whatever that

might mean) they are nonetheless deeply saturated by its “ternary”

grammar. For “it is not possible

otherwise to pray lovingly out of a compassionate heart for one’s enemies,

unless, by our co-operation with the Good

Spirit and our contact and unity and contemplation of God, we have come

into the possession of ourselves as pure of every stain of flesh and spirit.”

(118). And earlier: “knowledge of these

things is for them whose intellect is illumined daily by the Holy Spirit on

account of their purity of soul, whose eyes have been clearly opened by the

rays of the Sun of righteousness, whose word of knowledge and word of wisdom is

through the Spirit alone…” (114). Indeed

Symeon even makes the somewhat startling claim that the catechumen stands

outside the church as one “who cannot reflect the glory of the Lord with the

uncovered countenance of his intellect.” (119)

(Not knowing what that even means,

I apparently find myself outside amongst the uninitiated!)

All

of this must not be reduced to mere epistemological questions, either. Rather this mode of knowing God, as God

initiates us into Himself, is the very form of salvation as deification. God is “encompassed like a treasure by the

earthen vessel of our tabernacle, the Same who is in every respect both

incomprehensible and uncircumscribed.”

Thus “Without form or shape He takes form in us who are small…This

taking form in us of the Good who truly is, what is it if not surely to change

and re-shape us, and transform us into the image of His divinity?” (120) Thus repentance “through confession and

tears, [is] like a kind of medicine and dressing, cleanses and clears away the

wound of the heart and the scar which the sting of spiritual death had opened

in it.” (123) Indeed in a disgusting

reversal of images sin is seen as an opening for the indwelling of the Devil in

us rather than God’s light, and this is represented under the figure of a worm

“who slips in immediately into the heart, and is found to dwell,” when one has

been “pricked by the sting of death which is sin,” and the Devil-worm slips his

way into the wound (123). In an even

more disturbing image (though rightly so), those who continue to sin, “actually

take pleasure in these wounds. Nor is

that all, but they are eager in fact to scratch them and add still other wounds

to them, thinking that health is the satisfaction of their passions.” (124). The ambiguous phrase “thinking that health is

the satisfaction of their passions,” seems to mean, to follow Symeon’s imagery,

that the sinner believes the momentary passion which finds alleviation in

scratching the itch (though aggravating the wound) is true health. This reversal of indwelling-imagery is in

itself a negative demonstration of the necessity for us to be caught up into

the Trinity by the Trinity itself to be saved.

Symeon

ends the Ninth Ethical Discourse with a question from his interlocutors that

reminded me of Plato’s paradox of knowledge in the Meno dialogues. In those

dialogues the question that Meno poses, and Socrates tries to answer, is how

can one learn if one has no previous knowledge of the object being inquired

into? That is to say, if I do not know

what I am to learn, how can I ever learn it?

But if I know it how did I know it without such learning? The question posed to Symeon is alike but in

a slightly different key: “’But you,’ says my interlocutor, ‘are you such a

[saint] yourself? And how shall we

recognize that you are such?’” (126). In

other words the question being posed is a culmination of a prior dilemma:

Symeon has accused his interlocutor(s) of meddling in knowledge they know

nothing of. If we are to follow Symeon’s

logic, this is not just due to a deficiency in their own understanding. Rather they do not possess the Spirit of God,

they are outside the church as catechumenoi

because they are not yet caught up in the mysterion

of the Trinity (125). How then are they

to identify Symeon as himself holy?

Because surely if they could do that, they themselves have the Spirit,

as sainthood is nothing else than the fruits of the Spirit in a person; and the

ability to recognize these fruits is again nothing other than the purification

of the Spirit in another. This thus

appears to put Symeon in the horns of a bull-sized dilemma: for if they can

recognize his authority to rebuke them, then Symeon’s rebuke is itself

destroyed, for they do in fact have the Spirit.

And if they in fact cannot identify Symeon as a holy one, then again his

rebuke is nonsensical and worthless because his claims to authority are

unverifiable.

Symeon’s

retort has a measure of comedy in it (though I doubt he would ever see it that

way). He admits to them that they cannot

identify him as holy, for they are worse off than old Isaac, who, though blind,

could still recognize the voice of his son.

But these doubters cannot even hear.

“How are you able to know a spiritual man? Not at all, certainly…If then you are also

fleshly because of unbelief and wickedness because of neglect and transgression

of the commandments, I say that you have fattened your heart and have stopped

up its ears, and that the eye of your soul has been veiled by the

passions. How in that case would you be

able to recognize a spiritual and holy man?” (126). However in an ironic way this attack that

admonishes his opponents for being both blind and deaf to God, far from being a

complete stoppage to their knowledge of God, has provided them with a first step. Because immediately after, Symeon goes on:

“My fathers and brothers, I beg you instead that we strive in every way for

each of us to know himself…for it is impossible for a man who has not

recognized himself before hand so as to be able to say with David, ‘but I am a

worm and no man,’ or again with Abraham, ‘I am but dust and ashes,’ to

understand any of the divine and spiritual Scripture in a spiritual way.”

(127). This is because no one “can

become even a receptacle of the Spirit’s charismata without meekness and

humility.” Thus in a delightfully ironic

turn of fate Symeon’s accusation that his opponents are blind and deaf turns

into, should their admission be forthcoming, the absolute possibility of vision

and sight.

Comments